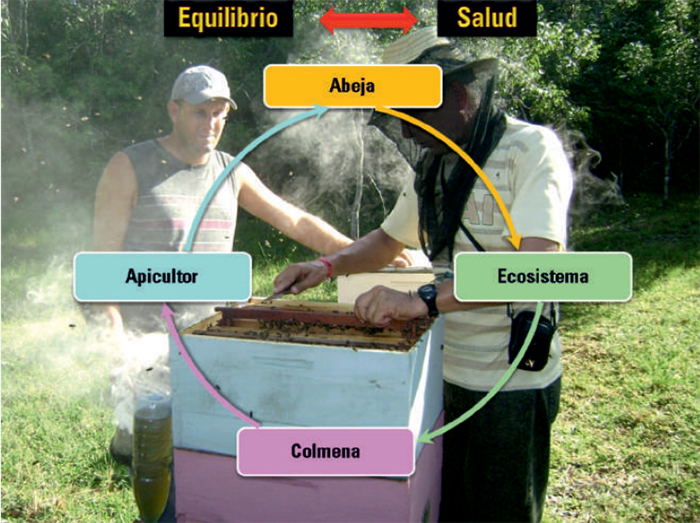

A beehive encompasses the entire population of individuals—the bees and the organic and inorganic elements—which, as a dynamic complex, interacts with the communities of plant and animal elements and their non-living environment. A single honeybee, from a productive standpoint, represents nothing and, as a life form, is ephemeral and without a future. The colony as a whole is the functional biological unit, which is related to and forms an inseparable part of the ecosystems it inhabits: it is, in itself, the basic functional unit.

The apiary constitutes the epidemiological unit.

The beehive, like a cow, has a “skeletal system,” made up of solid elements such as wood, wire, and nails. The reproductive system is represented by the queen bee, the drones, all the cells containing brood in any of its stages, and the brood chamber, which, like a uterus, houses the insect’s developmental stages until they emerge as adults.

One can even imagine a digestive system for the hive, formed by the sum of the digestive systems of the bees in the swarm, the food exchange behavior among them, plus the honeycombs where nectar is stored, dehydrated, and ripened, pollen is ensiled, or royal jelly is deposited. One can also assume an immune system that encompasses the individual defense mechanism of each bee, with the protection provided by propolis, an immunomodulator of the colony, a waterproofing agent, and a fixative for the movable elements.

The beehive is a complex organism, comparable to a higher animal on the zoological scale.

The wooden elements, wires, nails, and hand-worked honeycombs are equivalent to the skeleton of that animal. The hand-worked wax serves as support and could be associated with connective, adipose, or supporting tissue. The muscular strength of the hive will be the sum of the muscles of all the individuals that comprise it.

The wooden elements that make up the beehive in modern production systems are equivalent to, or can be compared to, the skeleton of a mammal. A poorly constructed beehive is like a defective skeletal system, putting the colony at risk of illness and death. Introducing a sheet of foundation wax could be compared to an organ transplant, and opening the hive to work on it is a surgical procedure—all with risks to the colony’s health if performed without considering good production and sanitary practices. Numerous other examples could be added to this proposed parallel. The aim is to associate the beehive with a complex animal, situated on a higher zoological scale, whose well-being must be guaranteed.

Modern animal production systems, including beekeeping, must guarantee WELFARE

in terms of the FIVE FREEDOMS:

- HEALTH AND WELL-BEING. Free from suffering, injury, or disease, ensuring prevention, early diagnosis, and prompt treatment.

- HIVE AND WELL-BEING. Free from discomfort, providing a suitable environment that includes shelters and a comfortable resting area.

- FOOD AND WELL-BEING. Free from thirst and hunger, ensuring easy access to fresh, clean drinking water and a diet to maintain health and vigor.

- APIARY AND WELL-BEING. Free to express normal behavior, providing sufficient space, adequate facilities, and the company of other bees.

- GOOD PRACTICES AND WELL-BEING. Free from fear and distress, guaranteeing conditions and treatment that prevent mental suffering.

When the purpose is to assess well-being, health or disease in beekeeping, it is necessary to consider the hive as a complex organism, with interconnected and cohesive systems to perform vital functions as a whole, where each insect constitutes “a cell of that complex”

The well-being provided to bee colonies can be assessed using the same indicators applied to other productive species, such as: colony longevity, reproductive fitness, productivity, number of individuals inhabiting the colony, susceptibility to diseases and recovery, adaptive responses to environmental or management changes, and mortality, to name just the main ones.

From the book: Beekeeping – Health and Production. Thanks to:

- Dr. Mayda Verde Jiménez

Apiculture Specialist. Member of the Food Hygiene Society of the Cuban Veterinary Scientific Council. - Dr. Jorge Demedio Lorenzo, PhD.

Professor of Parasitology and Apiculture. Doctor of Veterinary Sciences. Agrarian University of Havana “Fructuoso Rodríguez”. Ministry of Higher Education, Cuba. - Dr. Tomás Gómez Bernia, MSc.

Senior Specialist. Food Safety Group.

Master of Science. National Directorate. Institute of Veterinary Medicine. Ministry of Agriculture.

President of the Food Hygiene Society of the Cuban Veterinary Scientific Council.